Josie’s Place director honored for service to children in mourning

By Marjorie Beggs

Study Center Senior Writer and Editor

San Francisco, September 26, 2018

During a “talking circle” about change, Josie’s Place participants and facilitators share what they want to let go of from the past and what they’re looking forward to as the new school year starts. All photos courtesy Josie’s Place

Pat Murphy was surprised and flattered when Joe Hallisy, her friend of 40-plus years, said he wanted to nominate her for the prestigious Jefferson Award for Public Service in the Bay Area.

As co-founder and director of Josie’s Place since 2007, Murphy knew that her program was unique in San Francisco. Its free evening and school-based groups for children who have lost loved ones has served hundreds of grieving children and their families and trained 130 volunteers to lead those groups. Murphy and Andrea Bass, associate director, train clinicians and staff at local mental health agencies and schools on how to work with grieving children and teens. They also keep an extensive resource list of similar grief programs outside San Francisco, camps, national programs and literature. And Murphy and program volunteers provide critical incident response to schools and businesses following a loss in their community.

Despite capacity groups and increasing calls for Josie’s Place services, Murphy balked at the award idea.

“It was completely unexpected and I was hesitant,” says Murphy. “I thought about it for a few months but finally agreed.”

After that, things moved fast. Hallisy sent the nomination to the local Jefferson Awards Foundation on a Wednesday in August. The next Monday, KPIX-TV, a CBS affiliate and local Jefferson Award media partner, called Murphy to say she was an award winner. Ten days later, the station sent a team to Josie’s Place — a modest three-room space she rents in a church — where they filmed Murphy, a volunteer facilitator, and a mother and child in the program. The next week the two-minute segment aired multiple times on the station and on KCBS FM radio.

“What I see over and over is that kids touch grief, then step away. They grieve in small doses and then they go out and play.” — Pat Murphy, Co-founder and Director, Josie’s Place

The Jefferson Awards, established by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, U.S. Sen. Robert Taft and social entrepreneur Sam Beard more than four decades ago, honor people for exceptional public service. Besides the annual national awards, media partners — 125 newspapers and radio and television stations in 70 communities — make more frequent local awards to “unsung heroes” like Murphy.

Alaia Haberman, 9, holds the dreamcatcher she made — its webs catch the frightening bad dreams, common following a loss, and let the good dreams pass through. Kids keep the dreamcatchers by their beds at night, for protection.

Murphy, 70, a certified life coach, came to her work from her own experiences of death: She was 4 years old when her mother died of breast cancer and a young adult when her stepmother, who raised her, died. Both were named Josephine.

“I felt isolated and didn’t get the support I needed either time,” Murphy says, adding that despite more awareness of mental health these days, that kind of support still isn’t widespread. “It’s an issue that used to be overlooked entirely because children’s grief wasn’t understood well. The field is growing now, fortunately.”

Josie’s Place offers a twice a month, 90-minute evening group for up to 12 kids, ages 5-12, and another for teens only because their needs are different. Parents of both younger and older children meet separately, and most families stay in the program for two years.

“This isn’t counseling— it’s peer-to-peer support,” Murphy says.

The children tell their stories of loss in “talking circles,” and do art and activities that encourage them to express feelings like sadness, anger, anxiety. In a room together, they see how others are processing grief and recognize that they’re not alone. A 20-minute free time where the kids can let off steam before the group ends for the evening gives the kids time to transition to reality: Waiting at home are school work, chores and the place where one family member is gone forever.

“What I see over and over is that kids touch grief, then step away,” Murphy says. “They grieve in small doses and then they go out and play.”

Healing takes time. The touching and stepping away recede slowly.

While the youngsters meet, their parents share their experiences with death in an adjoining room. They learn how loss affects children at different ages and how to help them cope and adjust.

“The beauty of this model is the separate groups,” Murphy says. “Parents are foundational — if they know how to support their children and get support for their own grief, the kids have a better chance of adjusting well to the death.”

Josie’s Place also has offered grief support groups in nine San Francisco elementary, middle and high schools. The students meet for about 50 minutes during the school day. Murphy says the groups, once a week for eight weeks, are a critical part of her program’s services: For some kids, this is the only grief support they receive.

“We work closely with school counselors to find students who are most appropriate for a group. The groups can be challenging because there’s limited time for activities — we have to leave time at the end for the kids to defuse before they return to class.” Emotions run high in the groups, and facing fellow students immediately afterward is difficult and even embarrassing, especially for peer-sensitive teens.

It’s also hard to get teens to agree to join a group in the first place and to keep coming.

“Some of them won’t even look at me at first,” Murphy says.

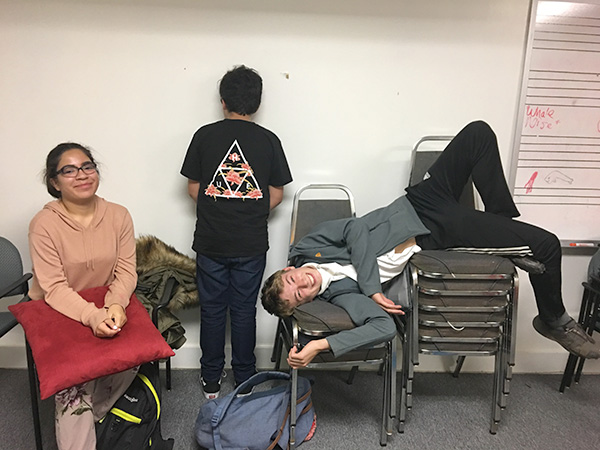

Three teens at Josie’s Place, from left, Brianna, Gabriel and Dylan, chose their own poses for this shot.

She recalls one young teen in a Josie’s Place evening group who had been referred by her school counselor because “the joy had gone out of her life” after her father died. Depressed and isolated, she wouldn’t make eye contact with Murphy at first.

“But once she was in the group, her demeanor changed fast,” Murphy says. “She even took a younger group member under her wing.”

The counselor told Murphy, “I don’t know what you do there, but her change is magical.” Murphy prefers to see the change as what’s possible with time, care and support.

Murphy, Bass, the other participating kids and their parents all contribute to that support, but it’s the volunteer facilitators, who have lost family members themselves, who Murphy calls “the heart and soul of our groups.”

“There is so much connection and play and tenderness in the process of grieving as a group,” wrote volunteer Emily Adams in the program’s spring 2018 newsletter. “I feel a collective sense of relief when we all sit down together and no one has to explain what it means to lose someone significant, because we all know everyone in the room gets it. Together we get to feel we are strong because of loss, the fact that we are in a community because of loss, that sense that we have this opportunity to heal because of loss. We get to see how we hurt, but we are not broken.”

Despite the successes of Josie’s Place, a fiscally sponsored project of San Francisco Study Center, Murphy isn’t sure she wants to change much about its modest structure. She’d like to offer groups in more settings, like Boys & Girls Clubs. But for participants, she thinks a twice-a-month group works best because it reinforces the idea that grieving families will heal. Meeting more often could become a burden for kids, so busy with after-school activities, and working parents, already struggling with complicated schedules.

“The goal is to support the families so they can get back to as normal a life as possible after a death,” she says. “We want them to integrate loss into their lives at their own pace.”

Marjorie Beggs is the Study Center senior writer.